The capacity for the eye-hand-brain to work in concert is called visuomotor functioning, spatial planning, and visual organization and processing. The capacity to see things as they are and to understand them belies the cognitive component involved with driving a motor vehicle. When driving a car, operators are expected to be alert, have full field of vision, and preserved capacity to make quick and easy decisions. Some of our driving acuity begins to change as our attention and speed of processing wane. As we age sensory input changes. I often encourage family members to have a driving evaluation when negotiating over who should drive. These lessons take the decision over who is a safe drive away from a husband or wife placing it on the driving instructor. After a stroke, it is possible to regain driving privileges but the driving evaluation with a driving school it takes the decision away from family members.

Category: clock drawing

Australian TV: “Ask the Doctor” looks at a clock first published here

The clock drawing has become something of a cult following. It is curios and fun to look at the drawings produced by ordinary individuals. Most do very fine but some have difficulty on the task. I have published dozens of clocks in these pages and was approached by the producer of the Australian TV program “Ask the Doctor” if they could use one of the clocks I published. There are no defining elements that might expose the confidentiality of the patient in the show. I have been given permission by the producer to show the piece that was aired on Australian TV over a year ago. It is a show on Alzheimer’s Disease and is quite interesting.

Spatial planning and the clock drawing: Strange times in cognitive functioning

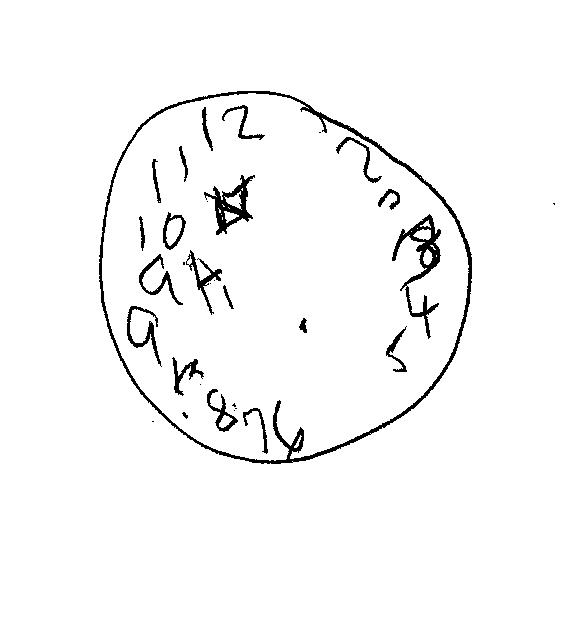

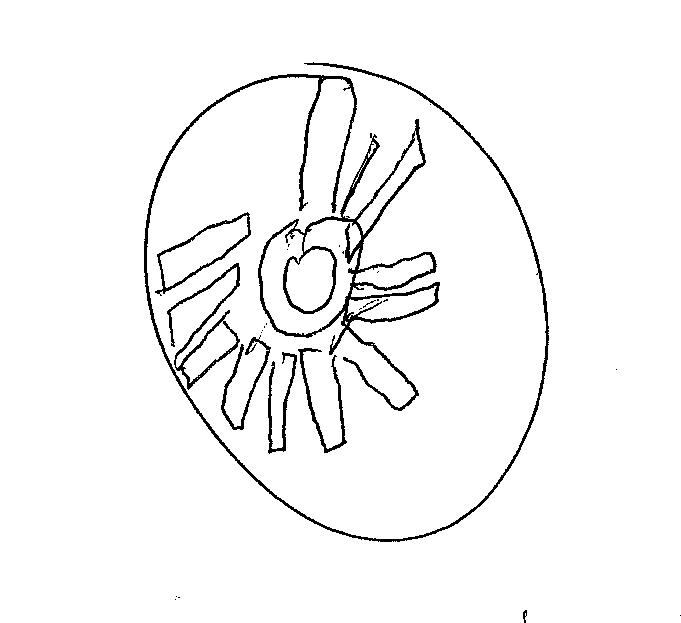

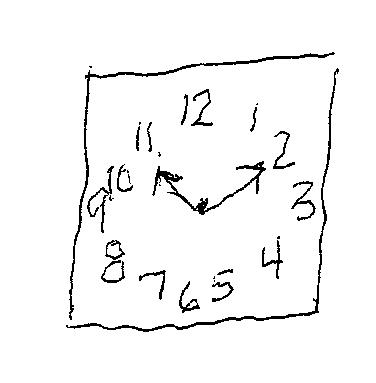

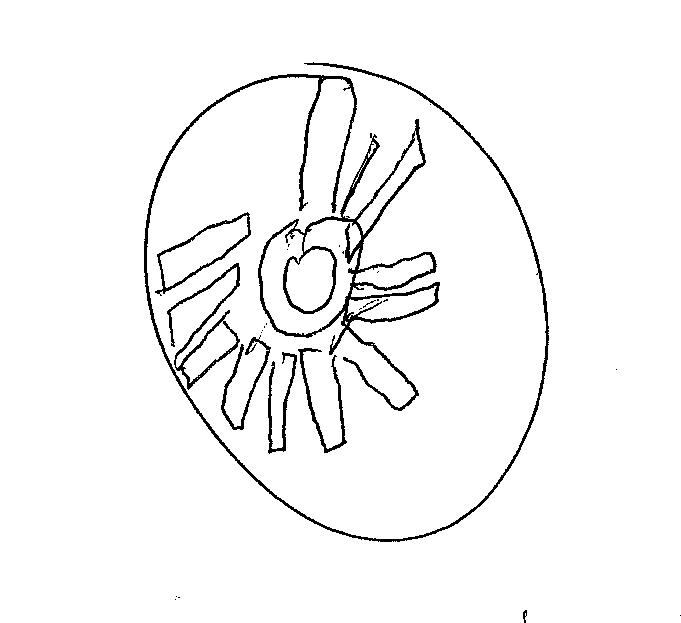

The clock drawing is one component of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment test published by Pearson Products here in the US. It is a useful method of screening for change in cognition among an older population. It is useful to assess cases of suspected dementia. The Clock of the week consists of an interesting array of hands pointing to each number. I am unsure what triggered this 71-year old to craft the clock in this manner.

When is see my cases at Whittier Rehabilitation Hospital in Westborough, MA I am usually struck by one person or another saying “Are you going to ask me to draw a clock?” The speech pathologists at WRH usually ask for a clock drawing in conjunction with the initial evaluation.

For whatever reason some of the patients who are assessed are able to remember the clock drawing and are surprised at its importance or utility in assessing cognitive functioning. Yet, if you look at some of the clocks I have published in the past 12 months they are certainly indicative of strange times in cognitive functioning. Most of the clocks I highlight illustrate a poignant depreciation in mental awareness and self-monitoring. People ask me “why does the patient have such trouble drawing a clock? Can’t they remember what a clock is? Why would they draw so many hands on the clock face?” The answer is the loss of functional capacity and its impact on everyday activities. If someone fails to correctly complete a clock drawing they will have difficulty at so many more tasks of independence.

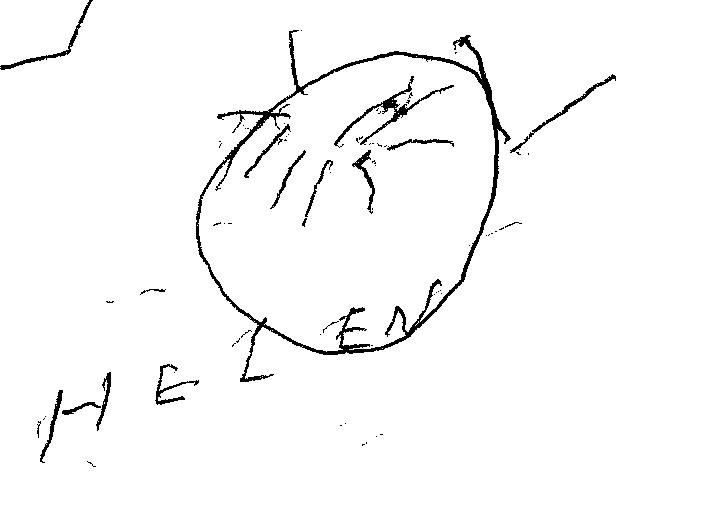

Actually, the clock of the week today illustrates the decreased appreciation of error awareness and cognitive inflexibility. The clock itself looks fine but when the third step is required e.g. setting the hands, the patient lacks fundamental problem solving and error detection.

Vote for clock of the year!

If you are interested in the clock drawing and casting a vote for clock of the year you may contact me at msefton@whittiehealth.com or by leaving a comment in the space provided at the bottom of the ballot. I look forward to hearing from you.

Successful clock? By now you all know.

What do you think about this clock drawing. It looks pretty good from the execution of the circle but you see the number placement is slightly off. Hmm? What do you expect perfection? Well truthfully yes the clock drawing is a task that should be quite routine – even when you are 70, 80, or even 90 years of age. Now the time it takes to complete the task varies from person to person and co-occurring illnesses, etc. As you watch this video what do you think about the hand placement? Does the clock read 10 minutes past 11? Or is it off?

Michael Sefton

Delirium: confusion and behavior change after Traumatic Brain Injury

Delirium is a medical condition that often has a sudden onset and waxes and wanes in response to the environment and is poorly understood. It is common among cases in the intensive care unit. Over half of cases of traumatic brain injury (TBI) develop delirium during recover according to Maneewong, et.al. 2017. Delirium is a sometimes unrecognized condition that manifests itself as confusion and inattention. It occurs frequently after traumatic brain injury and is classified as hyperactive or agitated delirium that manifests itself as confusion, yelling, irritability, sometimes hallucinations and paranoia. There is also a variant of delirium that is equally worrisome known as hypoactive delirium that often flies under the radar. These patients are quiet and sleep much of the time. Both are agonizing for family members to observe and can be a harbinger of medical complexity that may interfere with and prolong recovery. According to the New England Journal of Medicine patients with a high incidence of coexisting illness are at greater risk for delirium (Marcantonio, 2017). The longer delirium goes on results in a reduced likelihood that a full recovery may be made.

Recovery from traumatic brain injury generally depends on the nature of the primary trauma, location, presence of coup and contra coup injury, diffuse axonal injury, and secondary injuries such as edema, intracranial pressure change, autonomic storming, and more. Long-term recovery depends on admitting score on Glasgow Coma Scale, duration of coma, and post-traumatic amnesia. Delirium during recovery from TBI may last from a day or days to weeks. Men are at greater risk of delirium that is sometimes linked to somatosensory loss such as poor sight and hearing (Marcantonio, 2017). Delirium has significant a consequence on cognitive functioning and will impact working memory, concentration, and all higher order functions including problem solving. Another term is encephalopathy. It is a common manifestation in patients with non-traumatic underpinning including sepsis (infectious illness) such as pneumonia and urinary track infection, delayed hemodialysis, and many others. In refers to brain dysfunction often due to multifactorial issues including metabolic and infectious causes. These are treatable causes and generally do not exhibit the combative agitated behavior seen in those with traumatic brain injury (Sefton, 2016).

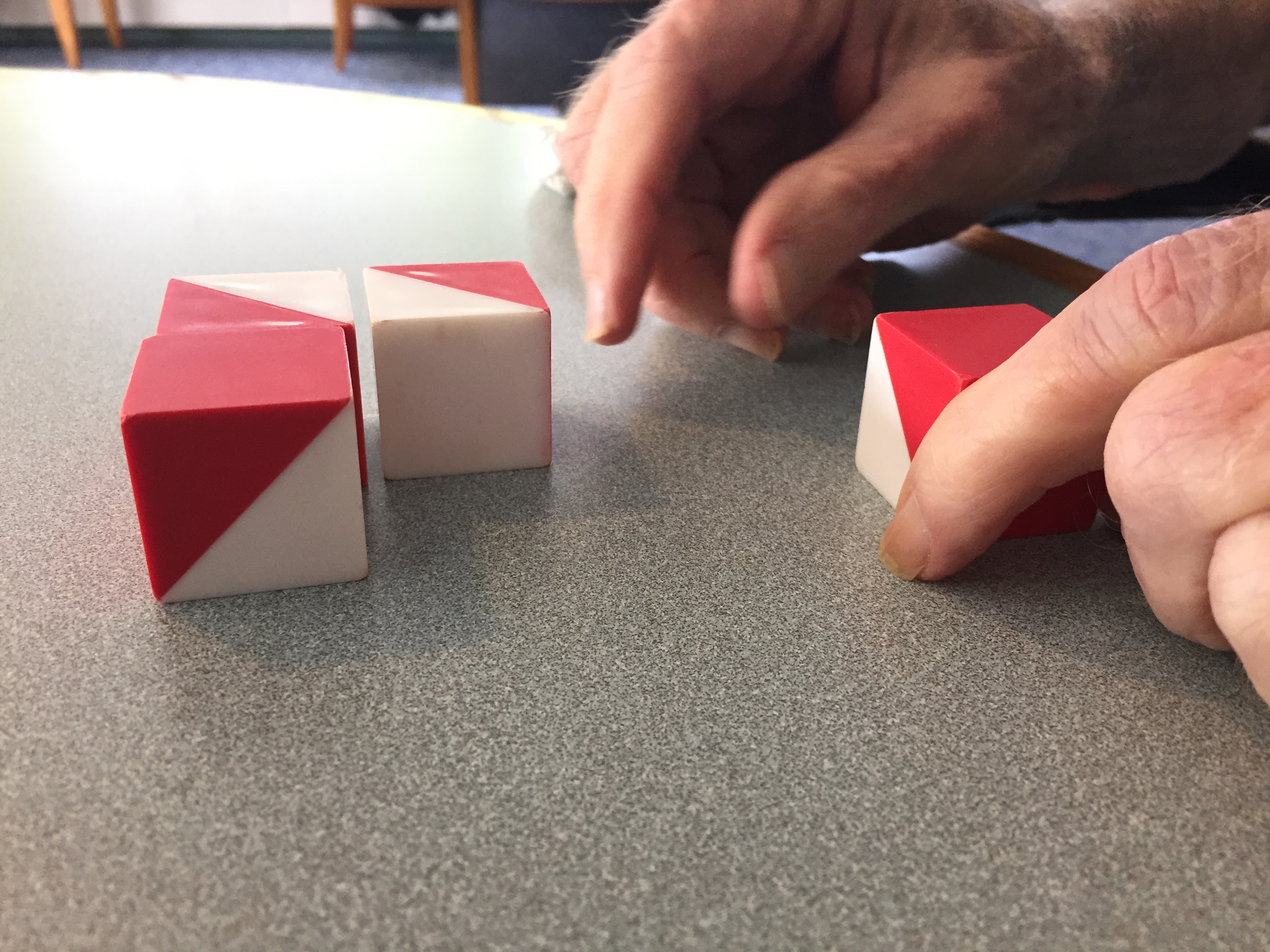

BLOCK DESIGN – PHOTO MICHAEL SEFTON

Recovery and Return to Function

Rehabilitation units across the country are faced with recovering patients with symptoms of delirium and must manage the confusion and associated behaviors with the demand for acute rehabilitation that often requires 3 hours of therapy daily. According to the NEJM review there are 4 distinctive features of delirium including: an acute change in mental status with fluctuating course (waxing/waning), poorly deployed attention, disorganized thinking (confusion) and/or altered level of consciousness – as seen in hypoactive delirium. It can be a true emergency and often results in a trip to the emergency department. It is especially dangerous in the elderly.

A recent patient was admitted to the trauma center after a fall down the stairs. She was 75 years old. She had bleeding in her brain called a subdural hematoma that required surgery. She underwent a craniectomy which meant that part of her skull was removed to accommodate massive swelling. According to family members she was independent and loving prior to her accident. I will call her H.S.

H.S. had post-traumatic seizure activity – including status epilepticus that is often associated with high levels of mortality. She was quite badly injured and her older age put her at high risk of a poor outcome. The intractable seizure was eventually controlled with 750 m.g. of levetiracetam on which she remains in ongoing treatment. She was required to wear a helmet whenever she was out of bed in case of fall. Having no skull in place over part of her brain meant that any jostling to the head could result in further injury to the dura mater within the skull. Obviously, if you are wondering, the skin flap closes the cranial vault resulting in a significant deformity to the head. Upon admission to acute brain injury rehabilitation the 75-year old H.S. had hypoactive delirium sleeping most of the time. Gradually there became a window of time during which she was alert but passively non-compliant. At this point she was sent back to the trauma center for cranioplasty – the surgical reinsertion of the skull. From this point onward she has had significant, unremitting hyperactive delirium. The unremitting nature of her condition was sad because much of her confusion stemmed from a number of fears she experienced. I hated to think that she was acting out physically in a primal defense against some perceived threat to her existence.

The form this took was completely out of character with the pre-injury personality. This is an important distinction whereas some patients are nasty prior to injury and become nastier once brain injured. Medication and management of symptoms are prototypical during this stage of recovery. I judged her to be at Rancho Los Amigos cognitive scale IV – confused and agitated. Her behavior was agitated and any effort to engage her in conversation was met with profanity laden criticism and accusations that would have made a sailor blush. She strongly denied having any pain.

“Patients with ICU delirium are less likely to survive and more likely to suffer long-term cognitive damage if they do.” STAT Boston Globe (2016)

The patient I am describing was initially given low-dose Xanex when needed. Xanex is a benzodiazepine class of pharmacotherapy and is usually avoided in brain injury recovery. It has little to no effect on her symptoms. She was next given quetiapine in low doses and after a short while it was increased to 25 m.g. twice a day. She was on a beta blocker for blood pressure control and excess adrenergic activity that can lead to autonomic storming. I think she may have tolerated quetiapine at higher doses but we never titrated beyond the last dose. At the same time H.S. was placed on adjuvant gabapentin as a mood stabilizer. She was on Sertraline for presumed depression given to her by a primary care physician. This combination was little to no help in the short run and the delirium worsened. Her behavior was agitated. She took out her tracheostomy tube and was able to verbalize immediately. Fortunately she no longer required ventilator support for breathing.

H.S. was seen by our geriatric psychiatrist over three visits. His recommendation was to discontinue the Sertraline, quetiapine, and gabapentin and start Risperidone at 0.25 m.g. twice daily and add Depakote. Meanwhile she was kept on levetiracetam for prior seizure activity. A levetiracetam level was ordered and as of this post is pending. The clock drawing below illustrates the global nature of the cognitive sequelae from delirium and TBI.

The outward behavior was driven by both internal confusion and external distraction. She believed she under threat by unknown people entering her home. Efforts to point out environmental cues that she is not in her home were unsuccessful. Her behavior was redirected and she was supported for her fear with staff efforts to gain her trust. She was both wanting her children and angry at them at the same time. Team therapists mentioned that she seemed to be having a conversation – with herself. Indeed, she was heard arguing with herself from within the veil bed in which she was placed for her safety. H.S.’s daughter was distraught at her mother’s change in cognition and behavior. She could not reach her on an emotional level.

Maneewang, J., Maneeton, B., Maneeton, N., Vaniyapong, T., Traisathit, P., Sricharoen, N., and Srisurapanont, M. (2017) Delirium after a traumatic brain injury: predictors and symptom patterns. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 13:459-465.

Marcantonio, E. Delirium in Hospitalized Older Adults. (2018) NEJM 337; 15.

Sefton, M. (2016) What is encephalopathy? Blog post: https://concussionassessment.wordpress.com/2016/10/06/what-is-encephalopathy/ Taken 11-10-2018

Clock of the week

One of the clocks previously published here at the Concussion Assessment and Management blog was chosen by the Australian Broadcast Company as an illustration of how dementia effects cognition in older Australians. I was contacted 6 months ago by the show’s producers. I think they struck by the simplicity of the task and the variety of responses we see clinically. The program called “Ask the Doctor” is a weekly broadcast in Australia about varying health concerns faced by the aging population down under. Like here in the United States, health concerns including Alzheimer’s dementia are covered by the producers of the show. I was sent a link to the show and have asked permission to post the broadcast that contains the clock drawing. It shows how important it is to understand cognition and dementia. I will post a link to the You Tube video of the original clock drawing below.

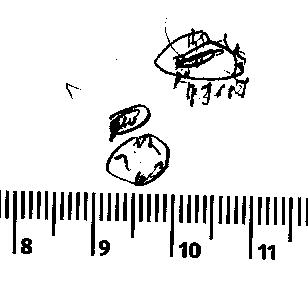

The Clock of the Week is drawn by a 65-year old male who is struggling from the effects of respiratory failure and its impact on debility. He has a tracheostomy tube in place and cannot speak. He communicates using gesture such as when he is thirsty. He is irritable and was eager to write to me when given the chance.

Here is a sample of his written language output. He was asked to write the sentence “Baseball players are tough”. You can see from the writing above that he put forth his best effort but still has a way to go to use written output as a bona fide communication modality. In cases such as this the clinical team is asked to use Yes/No inquiry to assess his language and for gaining deeper understanding of the physical and emotional adjustment through which this man is going. He is participating in treatment in spite of his frustration, anxiety, and thirst. Once he is able to swallow he will be given a hospital diet by mouth. Until then he receives full nutrition via a gastronomy tube in his stomach.

Here is a copy of the You Tube video that depicts the clock that was used on the Australian Broadcast Company “Ask the Doctor” program that was broadcast in October, 2018. In Australia there are thousands of new cases of dementia diagnosed weekly. Watch the video and share it.

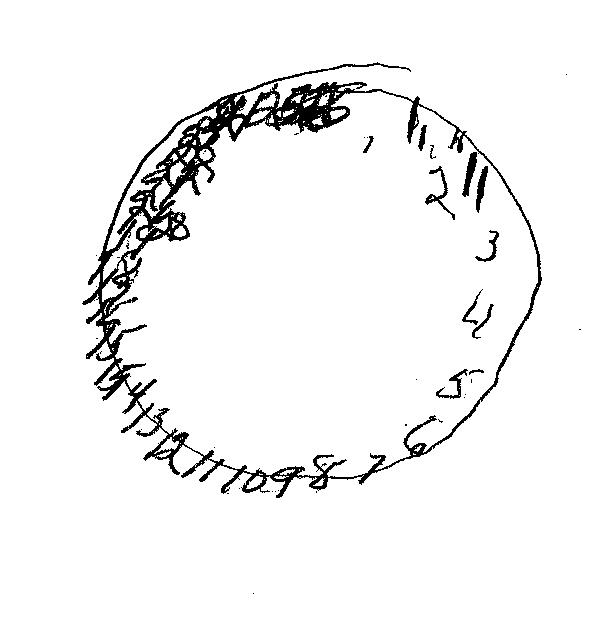

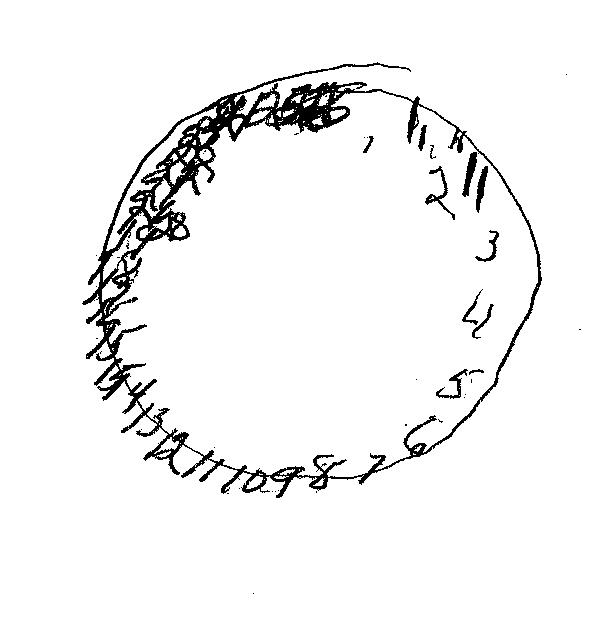

Clock of the Week: 8-15-18

Westborough, MA August 15, 2018 The clock of the week is submitted by a Speech Language Pathologist working with patients here at Whittier Rehabilitation Hospital. The patient who constructed this weeks prize winner is a 64-year old male with bronchiolitis obliterans, a lung disease characterized by fixed airway obstruction. Inflammation and scarring occur in the airways of the lung, resulting in severe shortness of breath and dry cough according to Wikipedia (2018). Just looking at the clock it may be safe to say that there is significant cognitive decline and/or altered mental status depicted in the lack of appreciation for the task demand. It is not clear to what extent his lung disease may have left him vulnerable to the effects of hypoxia – the lack of oxygen in the blood. Depending upon how long the brain goes with depleted levels of oxygen and how low the oxygen saturation drops can have a great deal of impact on anoxic brain injury.

Anoxia has a profound impact on cognition and functional independence. I want to thank the astute speech language pathologist for obtaining this clock drawing in the course of her patient assessment. I am curious as to what treatment options and methods she may be using with this interesting patient. I would welcome other clock submissions.

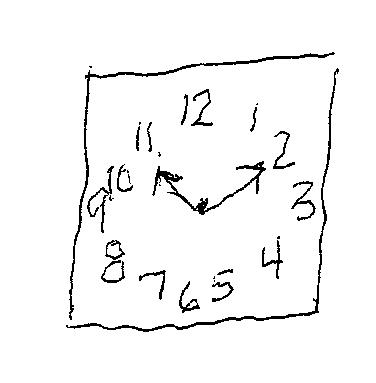

Clock of the Week: Alzheimer’s

WESTBOROUGH, MA August 2, 2018 Here is the clock of the week. It is drawn by Helen, an 84-year old right handed woman suffering from the affects of Dementia of the Alzheimer’s Type – DAT. I have published weekly or monthly clocks on these pages for the past 3 years. Recently I have added links to the video taken in our Neuropsychology service at Whittier Rehabilitation Hospital.

All HIPPA compliance rules are followed in terms of patient confidentiality. I encourage readers to send in clocks for me to publish. Helen had significant difficulty constructing this clock. Unlike some of the recent clocks I have published this clock was normal size. Helen had a resting tremor that closely resembled the movement pattern seen in patient’s with Parkinson’s Disease.

Clock of the Week: July 23, 2018

WESTBOROUGH, MA July 24, 2018 Some people believe that the simple task of drawing a clock is like a window into the brain (Eknoyan,et al. (2012). I have posted reviews of clock drawing over several years. Edith Kaplan, Ph.D. is credited with teaching me the importance of these neurocognitive protocols in 1985 while I was training at Boston City Hospital. Dr Kaplan saw the clock drawing as a parietal lobe test (Kaplan, 1988) but many debate that focal attribution of the clock drawing may under represent the clinical utility of this perfunctory task. Tranel and collegues (2008) found that the clock drawing has several potential neuropsychological correlates represent the neuroanatomic underpinnings of the individual clocks scored and rated in their research.

“Documenting the type of clock-drawing errors can contribute to the clinical evaluation of patients with suspected neuropsychiatric disorders and syndromes” Eknoyan, et al.

Watch the video below and enjoy a complete assessment of a single patient undergoing neuropsychological assessment. Post your thoughts and let me know what your observations say to the underpinnings of cognition we are seeing. This patient was cooperative and friendly. He is only 82 years of age and was undergoing treatment for a recent mechanical fall.

Michael Sefton

References

Eknoyan, D. et al. (2012) Journal of Neuropsychiatry Clin Neuroscience, 24:3 Summer.

Kaplan, E. (1988) The Process Approach. In Boll T, Bryant, BK, editors. Clinical Neuropsychology and Brain Function. Washington DC, APA.

Tranel, D, et al. (2008) Does the Clock Drawing Test have Focal Neuroanatomical Correlates? Neuropsychology, 22(5) 553-562.